The following excerpt was published by Trend magazine in the 2019 Summer edition and can be read in it’s entirety here: Click here

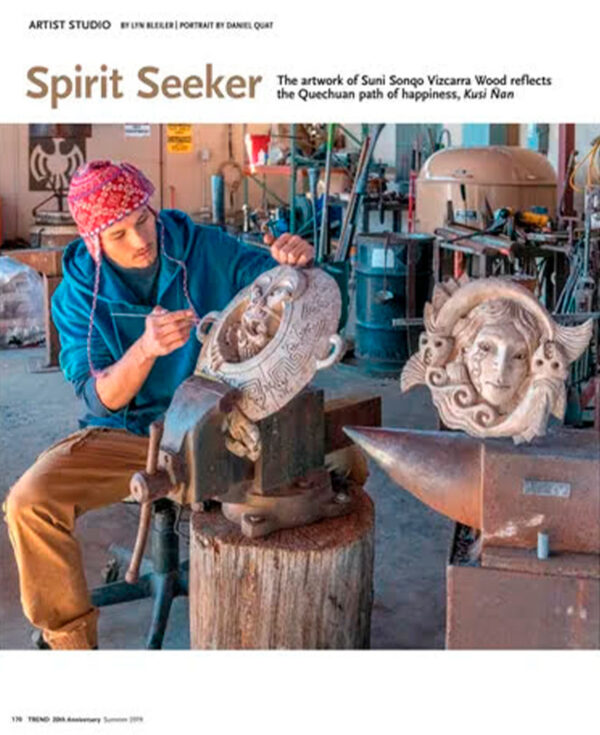

An artist born in Taos, New Mexico, and raised in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas would no doubt be a creator of art that celebrates the natural and spiritual. Suni Sonqo Vizcarra Wood, 22, wears a long braid, a warm smile, and a traditional Peruvian ch’ullo – a variegated wool cap knitted by his uncle. Suni Sonqo means “generous heart” in the Quechua language. He is a member of the Quechuan community in Peru’s southern Andes, which is committed to reviving ancient ceremonial and agricultural calendars of the pre-Columbian traditions. “Together with a network of local and international indigenous Nations, we are dedicated to preserving our roots while embracing our future”, Vizcarra Wood says.

His Taos-born mother and Peruvian father raised him and his siblings in Taray, Cusco, but annual visits to Vizcarra Wood’s maternal grandmother’s house have made Taos their second home. “I was born in and old haunted adobe house that my grandmother lived in, and where my mother was raised. The backyard was on Native land with the river and willow trees. It was a very intimate birth on a beautiful, snowy January morning. I was created in Peru, had my first heartbeats there, but born in Taos”, he says of his history. “In my culture, we believe that where you are born, the apus – spirits of the mountains – will help to guide you. I have one apu in Taos Mountain and another one in Peru.” His favorite places in Taos include the hot springs near the Rio Grande Gorge, Taos Pueblo, and Lama Foundation. He and his sister attended Taos Day School and the Taos Waldorf School when the family spent time in New Mexico. “There was lots of creativity in these schools, which was not how the public schools in Peru are. I remember playing in the garden and learning about Nature”.

Read the article in its entirety on Issuu.com: Click here